3 - Performance As Composition

My structuring logic when it comes to improvisation is to present my sonic material and to repeat it for long enough to become familiar and then apply developmental processes to it. This fundamental performance strategy can vary from composition to composition, where depending on the dynamic context, I can apply, or not, some improvisation. It is possible that a piece can begin with an improvised section or could simply expose the written structure. Basically, my work is about being able to communicate the composition in real-time and it is also about being able to respond to the audience. Furthermore, there is a necessity to be seen while performing because even though there is not necessarily a focal point on the sound, there is a need to have one on the performer. One of my musical aspirations is to maintain a connection with the audience and this relates to the concept of ‘creative authenticity’ found in Simon Zagorski-Thomas’ article concerning functional staging and perceived authenticity in record production:

Functional staging is also fused with and involved in the maintenance of the audience perception of creative authenticity and of the music maintaining the appropriate sonic qualities of what perceived to be an appropriate listening/engaging environment (Zagorski-Thomas, 2010, p. 263).

There are risk-taking elements during the performance that will influence the development and the directions of the work. The risks come from manipulating the sounds in real-time and trying to push their musical potential. Also, playing with the audio effects on the sonic content can be done to exaggeration, such as too many repetitions. As a result, the musical flow can be lost, or we can steer the musical direction astray. Furthermore, doing improvisation can also bring their hazards. The improvised moments occur when I loop the sonic content and transform the timbral content rather than focussing on sonic progression. If materials get repeated for too long the audience loses a sense of immersion and flow and instead focuses on the development of individual sounds and elements. The improvisations are dependent on several factors that can influence or modify my interpretation; the acoustics of the location, my state of mind of the moment, and how many people listening. The composition will never be exactly the same and will therefore always bring a dimension of risk in live performance. Another element of risk is to include loops that are not dividable by the conventional “four on the floor” (referring to the bass drum, situated on the floor, which plays every single beat) pattern, sometimes they can be 6, 10, 14 bars long and I need to calculate the right moment to bring them or to remove them. Furthermore, I do apply reverb, shuffling or filtering effects to one or more loops, thus I have to carefully craft and mix these processed sounds in order to generate variety to the work.

Another element of risk is having a preconceived idea of what I think the composition will be and while performing it, realizing that I have to move away from my indented structure or intended means of delivery halfway through. For instance, during my performance at Electric Spring 2018, one piece was coming to an end and because of the reaction of the audience, I decided to extend the piece by repeating the last musical idea and pushing it further. The result was unprepared and improvised but it became a highlight in my career as a performer (we can watch full clip of the action here, or the moment of the reprise with this link). Practically, this example demonstrates the process being able to read the audience, to manipulate the length of sound when it is working and extend the musical passages.

Live performance is important for me in order to keep my music fresh, changing and different. It is a music that needs an audience. There is a mastery that comes with practice and it is a reason that keeps me looking for better ways to play and perform my work. Taking risk in a live setting has enabled me to improve and enhanced my composition practice, as well as my performance skills. I have made plenty of errors when performing but through perseverance and repetition I have been able to master the performance presentation of my pieces. I developed a way of composing that stems from all the risk-taking moments from my live performance, and without risk I would have never achieved that level of proficiency or developed the template in which I structure my pieces. EDM is a performed culture and ultimately, I want to create a magical moment, a moment that did not exist before, but has the ability to fit a moment so perfectly that will make me, and the audience live something unique and special.

This unheard-of moment, this unique experience is part of the desire I thrive for in a live performance. It is the live experience which has importance and less the recording of it (the recording is there to capture the magical moments when they occur and to keep a memory of it). I enjoy performing and improvising live because I like to respond to the audience. When I perform, the pacing varies to the needs of the audience and this is different to performing electroacoustic music where I cannot change the pace of a work. I prefer the tension between the performer and its audience; between what I think I can get out of my instruments and what the audience wants. While I perform, I have to explore and improvise to the point that I still have the audience engaged, this can be done by the control of the delivery and the pace that I have over the music. These risks are limited; I do not take risks with the tempo or the meter of the composition. It is a method of engaging the audience with the control of the pacing. I have a specific BPM and that is fine with the stylistic domain. It is about judging the pacing of intensity with the audience. It is to play with a variety of intensity, where some moments I want a climax and other times, I want a calm musical section. I have done performances with DJs playing at the same event and I have perceived that the audience reacted positively to more “organic” and “human” music than with pre-configured sets of commercial tracks that have a similar level of production. People resonate and connect more with that human factor than with generic DJ sets.

To add to the pitfall of live performance, I am using the “Kill switch” on my Novation controller for cutting out the bass frequencies from the sonic content and this is where I risk of cutting at the wrong time. I am using the “Kill switch” because it is an important auditory, visual and physical cue that interacts with the audience, it is communicated by the exaggerated gesture of my hands pushing down those buttons on the controller. This performance technique is exposed in Mark Butler’s introduction (2006, p. 3) of his book about the perceptions and performance world of EDM, where the DJ is working the audience and making a drop:

Sometimes (DJ Stacey) Pullen cuts the bass drum out. The audience turns to him expectantly, awaiting its return. For one measure, and then another, he builds their anticipation, using the mixing board to distort the sounds that remain. As the energy level increases, he gauges their response. A third measure passes by, and a fourth, and then – with an instantaneous flick of the wrist – he brings the beat back in all of its forceful glory. As one the crowd raises their fists into the air and screams with joy, dancing even more energetically than before (Butler, 2006, p. 3).

I want people to respond physically, bodily to my music. I can achieve this by creating a sense of pulse. Furthermore, I search for ways to interact and communicate with the audience. The removal of the bass frequencies helps me to engage with them throughout my performance. Hans Zeiner-Henriksen (2010) unveils that process in his article where he discusses musical rhythm in the age of digital reproduction:

This is particularly evident in dance music. On the dance floor, the impact of the bass drum is, for example, shown through a common technique used by DJs: its removal (or the filtering out of low frequencies). This has an immediate effect on the dancers: the intensity of their movement decreases, and their attention shifts to the DJ as they await the bass drum’s return. The DJ may keep the crowd in suspense for quite some time while slowly building up to the climactic moment when the bass drum is re-introduced and the crowd delightfully satisfied returns to the dancing (Zeiner-Henriksen, 2010, p. 121).

In order to generate a sense of immersion and spatialisation in a work, I use loops with either low, mid or high frequency content, which offer a feeling of spatial movement. Zeiner-Henriksen (2010) has observed this phenomenon in Björn Vickhoff’s study on emotion and theory of music perception.

Our understanding of high and low, up and down, above and below, and ascending and descending in music presumably informs this relation. Björn Vickhoff writes: ‘Although there are no obvious directions of melody movement, most listeners feel directions in music. When the melody is moving “upwards” or “downwards” you get a feeling of spatial direction’ (Vickhoff quoted in Zeiner-Henriksen, 2010, p. 128).

Another important thing that I want to create, is a sense of intimacy, where people are able to see my setup as I am performing. This can also be achieved during my Livestreams: the audience can observe my hands touching and moving the controllers, especially since I have added a second camera in order to focus on the gesture of my hands. The viewer can watch me do these things live, realizing that the music is crafted in real-time and it keeps them engaged because what they see is not pre-recorded. Sometimes, when I am completely involved with my music, I also dance and jump as I am playing. Thus, the physical correlation between sound and bodily movement is important to connect with the audience.

3.1 - A Case Study: GusGus’ performance setup

Growing up, I found myself very much liking music in a spectator (passive) mode. When I decided to take music seriously and also wanted to become a(n) (active) proponent of music, I asked myself this question before initiating my musical studies: Do I wanted to become a DJ? Furthermore, I also had in mind a quotation by Gilbert Perreira: “Be yourself; everyone else is already taken”[32]. Thus, I assessed that ultimately, I wanted to play my own music and not perform other people’s music. I knew this route would be a longer pathway to a musical career. I have heard plenty of successful DJs while evolving in the nightclub culture. Nevertheless, becoming a composer/performer was simply the natural progression for my personal artistic career.

Electronic music is generated in the studio, which functions as a compositional tool as well as a musical instrument (Eno, 2004, p. 127).

This quotation from Brian Eno (2004) supports the idea of the performing producer discussed in this chapter. The position of performing electronic music live has become a lifestyle and a way to emancipate and express myself. As with traditional instruments, the hours spent playing develop a proficiency that provides expertise and skills in order to transmit information (music) to the listeners. Over the course of this research, I have developed skills that enable me to create/play/perform music, comparable to a Jazz musician who can improvise on a ‘standard’ of the repertoire; the rendition will never be the same and will always bring something new to the re-creation. I appreciate the possibility of striving for an ‘ideal’ studio composition and to be capable of transforming it into a live performance while still retaining its essence. Thus, my work in the studio and in a live performance are two of the same kind; it is the same work yet different.

GusGus, an Icelandic band, have been musically important for me for over 20 years. Their performance setup has evolved throughout the decades and their current technical setup of hardware/software is something I am interested in emulating with regards to the arrangement of my musical instruments. The two main devices that constitute the core of their setup are an Akai Sampler/Sequencer MPC2500 SE and a 16 channel mixer, the Mackie 1604 VLZ-3 (see Figure 24 below). The first one contains all the sounds from each of their tracks. The mixer receives the audio loops from the Akai, i.e. Bass Drum, Snare Drum, Hi-Hat, Percussions, Synth Bass, Synth Melodic and also Voice. In this way, Biggi Veira, the member of the group that controls these instruments can arrange and re-arrange the musical elements as he pleases. This offers a flexibility over the clarity and selection for the musical focus. Along with the singer(s), they interact with each other (voice and instruments) in order to play and synchronize between the different parts (intro, verse, chorus, break, outro, etc.).

Figure 24 – GusGus Live setup for performance: Sampler, Controller, Filters and Effects, 2017.

To make their music more organic, they have implemented a variety of sound effects that help them improvise with the materials of the pieces during the performance. This is done with a Doepfer filter unit that consists of a Voltage Controlled Filter (VCF), Low Frequency Oscillator (LFO), Voltage Controlled Oscillator (VCO) and Voltage Controlled Amplifier (VCA), these units are used for generating sound, modulating audio signals as well as compression. This live setup offers a multitude of choices in order to transform and perform with their sonic elements. Compared to my setup, I have fewer options in order to manipulate individual sounds but works similarly; using a pool of loops from the specific track and transforming the pieces as I re-compose/re-arrange them. The main difference is that there is a group of looping materials which allows multiple sonic interactions in order to decide and influence the musical interpretation of a track. Similar to the way I approach my compositions, they do have album versions of their work and use improvisational methodology to perform them live. Here is an example of their piece Deep Inside from their album Arabian Horse in 2011 and a live version on the KEXP Radio show in 2017.

3.2 - Rethinking composition as Performance

The creation and manipulation of sound, along with the performance of sound in space, constitute two fundamental areas of interest that bridge the transition from instrumental music through analogue electronic music to, most recently, computer music. Spatialisation and interpretation in performance are constantly being re-evaluated and developed. In my research practice, I explore both of these aspects of music using new tools and technologies. In my practice, there are some similarities to the interpretation of acousmatic music, particularly the aspect of sound diffusion, using a stereo sound file or stems played on an array of loudspeakers. Although, fixed multi-channel pieces are sometimes performed with minimal intervention as all of the relative speakers’ volumes are fixed in the studio, I personally strive to take charge of the arrangement of sound in space, therefore playing and orchestrating the sonic elements in the concert hall.

Figure 25 – SPIRAL Studio, where these 3 rings of 8 speakers can be considered as a High Density Loudspeakers Array, 2018.

Invited as a guest editor for the Computer Music Journal, in 2016, Eric Lyon wrote about composing and performing spatial audio music on High-Density Loudspeaker Arrays (HDLA) (see Figure 25 above):

A small but growing number of computer musicians have taken up the challenge of imagining a new kind of computer music for the increasingly available HDLA facilities. […] In 1950, theorist Abraham Moles wrote in a letter to Pierre Schaeffer regarding the new practice of musique concrète, “As much as music is a dialectic of duration and intensity, the new procedure is a dialectic of sound in space, and I think that the term spatial music would suit it much better” (Schaeffer 2012). The advent of HDLA computer music gives us one more opportunity to realize this early vision of electronic music with great vividness, to the benefit of artists and audiences hungry for new immersive auditory experiences (Lyon, 2016, p. 5).

Furthermore, Lyon says: “composing computer music for large numbers of speakers is a daunting process, but it is becoming increasingly practicable” (Lyon, 2016). Compositions such as Jonty Harrison’s Going Places (2017)[33] for 32 channel audio and Natasha Barrett’s Involuntary Expression (2017) for 50 or more loudspeakers (as the work is for High Order Ambisonics) arranged above and around the audience, are working with specific and fixed pre-composed spatial movement with little possibility for any spatialisation during the performance. In comparison, electronic dance music producers are mostly triggering stereo tracks and shaping the music with EQs, filters, etc., but rarely give any attention to spatialisation in their work. Thus, in my work, I am trying to combine both; detailed spatialisation, live performance and the live manipulation of sound. I believe that having control simultaneously of these different musical aspects allows a greater interaction with the audience while performing.

The live performance of my music is essential for me and this is why I am not presenting fixed 24 channel spatial music. As a result, my choice of software and use of hardware are determined by what I want to do. My experience as an acousmatic composer brings in a whole range of influences, approaches to space and thinking about sound that is different from those producers who came to music from a more commercial route.

I am intuitively thinking about form when I improvise/perform a composition, even if my sonic style leans towards a certain music structure or form. I consider this different from a fully organised and planned composition. My work has a form and shape arising from my pre-compositional and in-the-moment decisions. This can be a quasi-linear quality emerging from a progressive succession of loops, somewhat like a Markov chain. There are musical signposts and key points, where the musical elements are slowly transformed over time.

My acousmatic practice made use of an improvisatory sense of play in creating the initial sound material and I then took them into the studio, processed them and made them into a piece. Now I am curating samples and integrating my improvisational practice into the piece itself. I am trying to combine the behaviours of my acousmatic practice and develop sound in real-time during performance as equally important elements in my current practice. In regard to my music, this process demonstrates a sense of progression by transforming a sound and generating several versions of it as the piece unfolds. With my performance, I am trying to provoke the kind of sonic immersion and musical journey that the audience will experience within the concert space. These goals are reached through the transformation and organisation of sounds, plus the surrounding environment created by the loudspeaker array.

From the experience of my performance at Electric Spring 2018 and the HISS (Huddersfield Immersive Sound System) workshop during the summer of 2017, I was able to perceive how my spatial gestural thinking from the SPIRAL Studio could move to the HISS installation in Phipps Hall, a performing space at the University of Huddersfield. I was pleased to hear that the translation of my work from a smaller (studio) setup to a concert hall was not losing its sense of immersivity. I have noticed that the spatial movements were still accurate and precise as with my initial (studio) intention. My piece Rocket Verstappen (2017) has some sonic elements circling the speaker array at 01’37” counter clockwise on the upper ring of eight speakers and I could follow the direction and location of the sound precisely in Phipps Hall. Not all of the spatial translations were as exact or as intended as this one. For instance, in my work Chilli & Lime (2017) the introduction produced a different perspective on the diffusion of sounds in Phipps Hall than it did in the SPIRAL Studio. In this piece, a guitar loop is subject to various kinds of reverberation in order to play with the sense of space: a delay effect was added to the guitar loop which helps to expand the perceived localisation, making the sound feel as though it comes from beyond the speakers. Since Phipps Hall is a larger space (see Figure 26 below), the diffusion and distribution of sound energy was greater than in the SPIRAL Studio and it helped me to immerse the audience in moving layers of sound.

Figure 26 – Huddersfield Immersive Sound System (HISS) during Electric Spring 2018.

There is a functional difference in my loudspeaker setup when I compare it with the acousmonium’s orchestra of speakers which is front-of-stage oriented. I am using a dome of speakers surrounding the listeners rather than an acousmonium in order to create a sense of immersion. The idea of spatiomorphology (Smalley, 1997), so prevalent in acousmatic music, is not so pertinent to my music because the critical listening is not the same when you are moving and dancing, as opposed to when you are sitting down in an acousmatic concert:

EDM is made, above all, for non-stop dancing. Admittedly, it is possible to do many other things while listening to EDM, but it is the immersion in the intense experience of non-stop dancing, more than anything else, which defines its specificity, its operative nexus (Ferreira, 2008, p. 18).

My work offers a space that the listener can occupy in order to experience a sense of immersion, where there is sometimes a focus on certain musical elements. My music is not about a spatial interplay akin to Jonty Harrison’s work within the BEAST configuration. It is more ‘listener centric’ than focused within the music itself. The quotation below demarcates where the audience should be standing during a concert when comparing with Jonty Harrison or Christian Clozier (Clozier, 2001) are doing (seated and fixed, as opposed to be free to move around):

It is crucial to note that performance in EDM involves DJs and audience, humans and machines, in mixed proportions, for it concerns them not in their opposition but in their shared sonorous-motor reality. […] When sound meets movement in EDM's drive for non-stop dancing, DJ and dance floor, machine sounds and human movements insistently perform their shared reality (Ferreira, 2008, p. 19).

At the beginning of my research, I was only using 8 channels to create surround music. Progressively, I added another ring of 8 speakers (above the first one). Since the software’s (Ableton) audio configuration was limited, I finally found a solution where I could use the whole 24 speakers of the SPIRAL Studio (see Figure 27 below) by coupling the stereo audio files into pairs of speakers (front, right side, back and left side). This led to the development of my concept of ‘gravitational spatialisation’ that separates the audio frequency content according to their position on the frequency spectrum.

Figure 27 – SPIRAL Studio with its 3 rings of 8 speakers, 2018.

3.3 - Why 123-128bpm?

Humans are vibrational beings who are influenced by music. Music is produced by sound waves caused from traditional and virtual instruments. Being an ethical hedonistic person, my philosophy is deeply rooted in the self; my individual needs and wants are the most important things that will exist in life. Thus, I am striving to find pleasures and to maximize this sense of enjoyment; to do everything in my power to have an enjoyable life. Therefore, when I am composing or performing, I aim at reaching this feeling of aural satisfaction, to produce a musical environment where sounds provide a joyful, captivating and entertaining experience.

I am creating music for pleasure, be it physical or intellectual. Combining the two is my ultimate goal as a composer. The type of music I compose has a physical and emotive quality to it, but yet also a technical and intellectual aspect to it. In my work Cyborg Talk (2017), I play with the sensorial dimension with certain sounds (introduced at 2’21”) that are situated in the low frequency register, which have a visceral quality. These low frequencies, according to Richard Middleton in regard to the viscerality of sounds, affect us wholly:

just as physical bodies (including parts of our own) can resonate with frequencies in the pitch zone, so they can with the lower frequencies found in the rhythm zone. 'The producer of sound can make us dance to his tune by forcing his activity upon us', and when we 'find ourselves moving' in this way, there is no more call for moral criticism of the supposedly 'mechanical' quality of the response than when a loudspeaker 'feeds back' a particular pitch. Boosting the volume can force zonal crossover, as when very loud performance makes us 'feel' a pitch rather than hearing it in the normal way; our skin resonates with it, as with a rhythm (Middleton, 1993, p. 179).

Furthermore, these specific sounds spiral around our head in order to give a whirling sensation, to hypnotize us within this sonic immersion. Later on, when Part B is introduced (at 5’45”), I reduce the musical intensity in order to bring in two new sounds (trumpet sounds an octave apart). Putting these through a reverb effect creates the impression of a physical distance with the sound, that plays and appeals to a certain nostalgic feeling, a longing to a distant past, while these sounds are spatialised around the audience. This sonic texture continues until I reintroduce a strongly visceral sound with substantial low frequency content, and add it to the distant, nostalgic sounds, thus encompassing both physical and intellectual quality at the same time (Part A + B = C).

Viscerality, sound vibration and low frequencies are working in common in a sonic therapy called Vibroacoustic therapy. “It is a recently recognized technology that uses sound in the audible range to produce mechanical vibrations that are applied directly to the body” (Boyd-Brewer, 2003). The recognition of low frequency content as a potent vessel for physical sensation of sounds, provides a justification regarding my musical intention for including such sonic material in my work. The work of Mehdi Mark Nazemi supports this interaction between viscerality (physical response) and music:

One of the most natural responses of the human body to music is the synchronization of anatomical movements and other physiological/psychological functions with musical rhythms. Our body - through pre-conscious processes - is quick to recognize and “feel” vibrations, the foundation of what makes the rhythmic pulse. Our body senses the vibrational events, and we begin to interpret this sonic resonance as rhythmic events (Nazemi, 2017, p. 42).

Throughout my teenage years in nightclubs, I found that music that had a certain beat per minute (bpm) rhythm, situated between 123-128 bpm would make me dance more than the ones below (115bpm and less) or the ones over (130bpm or higher)[34]. Of course, there are always exceptions but generally there is a clear trend in the way I am naturally attracted towards certain bpm. These bpm are felt viscerally, and this is how they create a somatic (bodily) connection with me; the sound oscillations resonate with me. It is empirical evidence and observation from my experience with EDM. Trance music usually has a faster bpm and higher frequency content, whilst Hip Hop has a slower bpm, between 85-110 bpm.

At the beginning of the 1990s, I became interested in House music. It was different to most music I had heard until then. It was more fashionable than the commercial Dance music of that era. It was reaching, subliminally, those specific bpms that made me vibrate and connect with the sounds. House music’s most prominent characteristics, as defined by the Oxford Music Online website[35], demonstrates that the bpms most associated with the genre are exactly the ones I am striving for:

House […] feature a 4/4 meter (“four on the floor”), with a kick drum sounding on every beat. Ample use of hi-hats, as well as snare hits or handclaps on the second and fourth beat lend a syncopated “disco” feel to a steady kick drum pulse. House music borrows heavily from disco and soul—producers emphasized melody and vocals, and added embellishments such as drum fills and strings. The tempo of house music tracks hovers around 120 beats per minute (as opposed to techno tracks, which range from 120 to upwards of 140 beats per minute). The Roland TR-808 and TR-909 drum machines were often used to provide the drum tracks for house music. The Roland TB-303, a “bass synthesizer,” was often utilized by house producers for its unique timbres—the twitchy, rubbery synth lines produced by the TB-303 spawned the sub-genre of acid house (Dayal, 2013).

Within the House music community, it is well understood that it is hard to explain what exactly this genre is. Aficionados from the early days describe it as “House is a feeling”. In this excerpt below, Chuck Roberts preaches the gospel of House music in Fingers Inc.’s Can You Feel It (1988):

In the beginning there was Jack, and Jack had a groove. And from this groove came the grooves of all grooves. And while one day viciously throwing down on his box, Jack boldly declared: "Let there be house!" And house music was born. I am you see, I am the creator, and this is my house, and in my house there is only house music. But I am not so selfish; because once you're into my house it then becomes our house and our house music. And you see, no one man owns house, because house music is a universal language spoken and understood by all. You see, HOUSE IS A FEELING that no one can understand really, unless you're deep into the vibe of house. House is an uncontrollable desire to jack your body. And as I told you before: This is our house and our house music. In every house, you understand, there is a keeper and in this house the keeper is Jack. Now, some of you might wonder, "Who is Jack and what is it that Jack does?" Jack is the one who gives you the power to jack your body. Jack is the one who gives you the power to do the snake. Jack is the one who gives you the key to the wiggly worm. Jack is the one who learns you how to walk your body. Jack is the one that can bring nations and nations of all jackers together under one house. You may be black, you may be white, you may be Jew or Gentile... It don’t make a difference in our house. And this is fresh (Roberts, 1987)[36].

The impact of House music has influenced my musical aesthetic and sensibility towards visceral emotions; I need(ed) to feel the music on the dancefloor, I was looking to ‘Jack my body’, to be under the spell of the groove and beats of House music. Thus, when I am composing, I do intentionally aim at recreating those blissful musical moments where I could not resist the power of the percussive beats and to the DJ’s rhythm. The DJ would be manipulating us like a snake charmer or shaman and put us in a tribal trance in order to dance all night long. “Fans of House music may be predisposed to prefer faster beats and pulsating rhythms, or it could be that repeated exposure and a greater understanding the subtleties of the genre are what draw us to it.” (MN2S, 2016)

A more scientific explanation of this experience of House music is described here:

We all know that listening to music brings us pleasure and joy (and sometimes pain), but what is happening inside our brains when we listen to it? The answer is: a lot. When you hear a song, all four lobes of the brain react. Memories, emotions, thoughts and movement are all impacted. Your brain processes the tone, pitch and volume of the music in the auditory cortex, then sends this information to the rest of the brain, creating a richer experience. When it gets to the amygdala, your brain releases dopamine: the chemical behind rewards and pleasure.

Considering the many subgenres of house and wider electronic music, it is not surprising that house music can affect your brain in many different ways. Other forms of house and electronic have other effects. The release of dopamine, the pleasure chemical, is found to be greater at so-called ‘peak emotional moments’ in a song. The level of reward at this moment of peak emotion is thought to correspond to the length and intensity of anticipation during the build up (MN2S, 2016)[37].

Furthermore, the frequency content of House music shares common sonic characteristics with Hip Hop music; they both “fill up the lower side of the EQ spectrum with wide 808 booms and bass” (Benediktsson, 2010)[38], which I appreciate as much as the mid and high frequency sonic content. These bass sounds seem to affect the lower portion of our body, which makes the hips move and groove to the music. In comparison, the sonorities of Trance music affect cerebral neurons, thus making the head nod back and forth.

3.4 - Physical response

The musical connection I have with my work exists on a physical somatic (relating to or affecting the body) level as well as an intellectual one. This also extends to the structured and improvisation musical segments where I can combine these two conceptual pleasures. There is a somatic-cognitive creative loop, where I am sonically pleased with the sounds therefore, I consider how I can continue developing these materials further and that makes me feel even better. It is through this process that my compositions developed from being, on average, 8 minutes to 10-15 minutes long and then even longer (up to 50 minutes). I am trying to find a balance between the physical and intellectual, creative and reflective, real-time and non-real-time, static sound and spatialised sound, structure and improvisation. I observed commonalities between my compositional methodology and the Greek doctrines;

the earliest concept of a balance of nature in Western thought saw it as being provided by gods but requiring human aid or encouragement for its maintenance. The natural balance implied relates to the rise of Greek natural philosophy where emphasis shifted to traits gods endowed species with at the outset, rather than human actions, as key to maintaining the balance […] Plato's Dialogues supported the idea of a balance of nature: the Timaeus myth, in which different elements of the universe, including living entities, are parts of a highly integrated “superorganism” (Simberloff, 2014, p. 1).

Personally, House and Techno have rhythms and frequencies (from 100Hz to 700Hz) that affect the core of my body, where my solar plexus is pulsating like a beating heart. It is my whole ‘central’ being that is moving and grooving to the tempo of those sounds; it makes my body vibrate in synchrony with the music. So, when I am composing/performing, I want to be completely involved and immersed with the sounds; mentally, physically and spiritually.

The advent of technology has had a tremendous impact on the speed of music. In the light of dance music from the 1970s and 1980s, disco music was based generally around instruments. Since then, the electronic means of producing music has allowed the expansion and increase in the tempo of dance music. As with lifestyle, ways of communication and transportation have become faster, music has also followed that trend. A professional DJ and producer C.K. stated "There was a progression as far as the speed of music is concerned. Anyone buying vinyl every week from 1989 to 1992 noticed this” (DJ Escaba Eskyee, 2015)[39]. For instance, in regards of Drum’n’Bass music, the Oxford Music Online website[40] mentions:

A genre of electronic dance music that emerged in the early 1990s in England. Drum’n’Bass draws on sampled drum breaks (typically from 1960s and 70s soul and funk records), heavy bass lines from Jamaican dub reggae, and a variety of melodic and harmonic material inspired by the genres of techno, hardcore, and hip hop. Its tempo is fast—often 160 beats per minute and higher—although many listeners perceive the bass lines as moving at half the speed of the drum breaks (Ferrigno, 2014).

We can hear some examples of this increase in bpm in music of Photek (Ni Ten Ichi Ryu, 1995)[41], Roni Size & Reprazent (Brown Paper Bag, 1997)[42] and Aphex Twin (Come To Daddy, 1997)[43]. Phoebe Weston (2017)’s article The Times They Are a-Changin suggest that Pop music is slowing down as people feel more reflective in 'dark times'[44] and, to corroborate this bpm trend, a Rolling Stone magazine[45] article from August 15th 2017 explains; “Producers, Songwriters on How Pop Songs Got So Slow”.

In an article by Blake Madden, he sheds light on studies about tempi in the range I have discussed and also considers why the body seems to prefer certain bpms (between 123-128bpm):

For improving physical performance, Dr. Costas Karageorghis of England’s Brunel University suggests music with tempos of 120 bpm to 140 bpm during exercise, when our hearts beat in a similar range. […] Dirk Moelants, a musicologist and assistant at the department of musicology at The University of Ghent, argues that a ‘preferred tempo’ around 120 bpm is a part of our biology. His 2002 paper for the 7th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition, titled “Preferred Tempo Reconsidered”, challenged psychologist Paul Fraisse’s previous conclusion that preferred tempo was somewhere in the range of 100 bpm (Madden, 2014).

The music that I have composed throughout my research does not involve lyrics, it is more oriented towards the creation of physical sensations. “If the constant 120 bpm average of charting pop hits represents our Platonic ideal of natural balance, then tempos far above or below that range represent the rest of the roller-coaster ride we call ‘life’” (Madden, 2014). Some popular examples of fast and slow bpm are:

The angst and nihilism of The Buzzcocks’ “Boredom” slashes through our ears at around 180 bpm. Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five paint the tension of inner-city life in “The Message”—one of hip-hop’s first bonafide hits—at around 100 bpm. Bette Midler regularly inspires waterworks with her 60 bpms ode to an overshadowed friend, “The Wind Beneath My Wings”. 120bpm is our safe place, and the further we get from it tempo-wise, the more volatile we become (Madden, 2014).

Thus, this is perhaps why I am drawn towards these specific bpm. Although there are no definitive answers or justification, these quotations provide some evidence that lends support to my empirical knowledge and experience, after 30 years of listening to EDM.

3.5 - Live Performance and Musical Flow

According to psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, focus and concentration hold the key to achieving ‘flow’. It is a term used to describe “feelings of enjoyment that occur when there is a balance between skill and challenge”, typically achieved when we are involved in a highly rewarding activity (Csíkszentmihályi, 1997, 1998). It is a process of having an “optimal experience; the state in which individuals are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter” (Csíkszentmihályi, 1990).

In my pieces, I can start with one sonic element and add another, and the combination of those two things stimulates a third and this then combines with a fourth that leads to a fifth and so on in the manner of a Markov chain. There is an ongoing stream of musical elements, so the progression seems musically logical; nothing really stands out as being a stark juxtaposition or a completely new thing since my music flows. It is a clear musical journey where nothing repeats but is one continuous sense of flow and movement, like a combination of previous elements to create or move seamlessly into the next musical idea.

I am creating a flow experience in my music that is actually key to expressing myself as a musician, through the sounds that I make rather than thinking about structure or melody. There is a rough goal or idea but that sense of flow, stream of consciousness, the experience and the real-time sound transformations in the present moment mean that I am looking at a different rendition of the piece every time I perform it. We need to be in the moment, to acknowledge all the elements of life and to go with the flow in order to access and achieve a sense of immersivity. We need not to let ourselves be concerned with details but to focus on giving ourselves over completely in order to be that perfect vibrational being, in sync with the elements of life. The way I perform allows me to react and to change the musical course in order to direct the music towards the vibe that fits the mood of the event, to what is happening on the dance floor, or it could be to reflect my own energy of the moment, which is akin to communicating my immediate feelings to the audience.

With diffusion, acousmatic composers have the security of presenting a fixed piece. I prefer to face the precarity of live music. For me, this creates a more meaningful in-the-moment emotional musical event which brings me greater satisfaction as a musician. At the Electric Spring Festival (2018)[46], I gave a performance and towards the end of it, I sensed that I was concluding the concert after one hour and forty-five minutes. At that moment, the audience responded in such a way that I felt as though I needed to carry on the composition a bit longer. This is one instance, where the sense of flow is not controlled by me but by the dynamics of the performance situation itself.

Although DJs are not specifically mentioned in his discussion of optimal experience, what Csíkszentmihályi calls ‘seamless flow experience’ resonates uncannily with the DJ (producer performer) practice of programming dance music:

Ultimately, contemporary DJs (producer performers) charged with programming dance music may be regarded as humanistic visionaries, presenting and performing music in recognition, reaffirmation and celebration of those qualities that are associated with happiness, meaningfulness, fulfilment, and pleasure. Music programming, then, is an aspect of DJ musicianship that may be considered both artistic and salubrious (Fikentscher, 2013, p. 145).

The DJ [performer] is heard rather than seen and she or he is positioned as a communicator, as the vibration of the sound engages dancers kinetically, while the visual field is effectively distorted, even destroyed, enabling the participants to lose themselves into the relentless yet meditative repetitive rhythms and washes of synth sounds:

The studio producer is increasingly seen on stage with a laptop with music mixing software, improvising with the recorded ‘stems’ of their music or, as a DJ, mixing their own recordings with related music productions. Whereas the traditional DJ is a researcher, archivist, occasional remixer and interactive performer, the producer-DJ is a composer, a technician and a (sometimes self-absorbed) performer (Rietvelt, 2013, p. 89).

The objective of the performer is to translate the energy and the sounds from his music into an apparent execution of his skills with the use of musical technology:

According to this perspective, performance in EDM is not a question of localized agency, but of the effective mediation between recorded sounds and collective movements, and the performer-machine relation is not a matter of opposition but of association and transformation in the technological actualization of the sound-movement relation. We could say that, in EDM, performance corresponds to this actualization: human movements making visible what machine sounds are making audible […] EDM DJs since then have increasingly found in machines the means to refine their control over the selection and reproduction of sound, thus improving the intensity and efficacy of their relationship with the dance floor.

In the case of EDM, it seems evident that the dance floor is a very important part of the media chain through which sound is transduced, the others being vinyl records, electric wires, loudspeakers, etc. In other words, when the sounds coming out of the loudspeakers meet the movements of the dance floor, one becomes a medium for the transmission of the other, and it is this short-circuiting of machine sound and human movement that seems to constitute the specificity of performance in EDM (Ferreira, 2008, p. 18-19).

The craftmanship required during a live performance is as important as in any other musical practice. The greater freedom I have over my composition during the rearrangement of their development, the more vulnerable a position I am in while performing. I can obviously make mistakes during my Livestreams but they do not make my work less interesting they actually provide a point to rebound from and allow for a different musical direction to use them as an actual intentional moment in order to make them fit in the grand scheme of my composition or improvisation. Actually, I abide by a famous phrase attributed to Ludwig van Beethoven: “To play a wrong note is insignificant; to play without passion is inexcusable”. This citation is definitely an integral characteristic of my performance. It is possible that the quotation is intended as a snappy summary of Beethoven's beliefs as reported by his piano pupil Ferdinand Ries:

When I left out something in a passage, a note or a skip, which in many cases he wished to have especially emphasized, or struck a wrong key, he seldom said anything; yet when I was at fault with regard to the expression, the crescendo or matters of that kind, or in the character of the piece, he would grow angry. Mistakes of the other kind, he said were due to chance; but these last resulted from want of knowledge, feeling or attention. He himself often made mistakes of the first kind, even playing in public (Rosenblum, 1991, p. 29).

Thus, the capital goal while performing and composing is to be in the moment; to be present with all ears and all mind. The necessity is to be at the service of my art in order to provide the right channelling for the musical offering since I am the mediator for the music to become alive.

A practical application of this system is to setup the SPIRAL Studio ready for performance, with the lights put into the ‘concert’ mode (see Figure 19), my library of sounds at close hand, having all the elements to make the magic of music take place (space).

3.6 - Methodology for the emerging artists

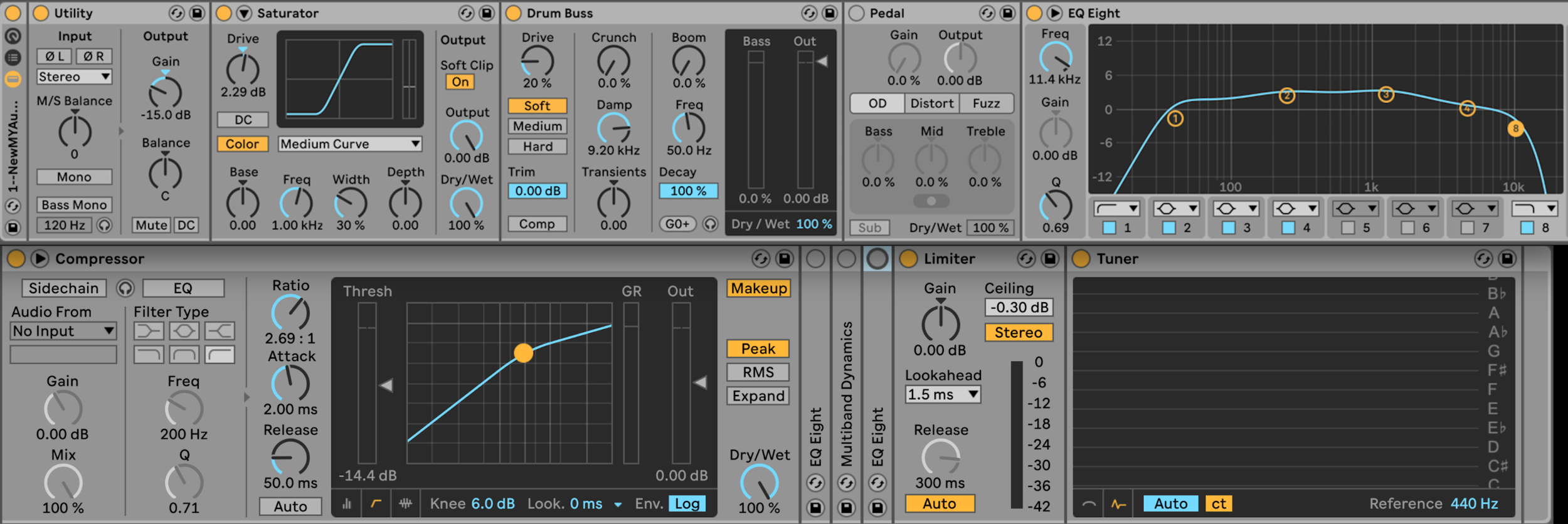

My elaboration of a performative work starts within the Ableton digital audio workstation (DAW), using a personal template. This template (see Figure 28 below) consists of several audio effects combined into one audio rack and this is applied to each of the eight tracks I work with. Each of the eight tracks contains multiple audio clips.

Figure 28 – My Audio Effect Rack in Ableton Live, 2019.

The first effect implemented is called Utility, which is a simple amplitude reduction of the audio files to -15 dBs. Since this type of music is often boosted in order to sound loud in nightclubs, I find it wise to reduce everything initially before increasing the loudness of the individual tracks within the mix. The second effect is named Saturator, which provides an initial boost to the sounds without going into overdrive or distortion. The following effect is Drum Buss which was developed in order to ‘pump’ the drum parts and make them sound more impactful – this boosts the bass and transient attack. Also, I have included a pedal effect, in case I wish to distort or fuzz the sounds. The next effect is called EQ Eight, which allows me to see the analysis of the frequency content of the sound and remove/boost specific frequencies. Then, a compressor intensifies the audio signal of the loop, which helps to make the sounds more present in relation to the others sounds in the mix. Additional EQ Eight and a Frequency Band Compressor are available if needed in the Audio Effect Rack. Finally, a Limiter stops the sound from distorting in the final mix. A Tuner is also included in order to find the central tonality among the audio loops.

Figure 29 – Ableton session of 8 audio tracks template with the Novation Controller, 2019.

The session comprises 8 audio tracks. I use the Ableton Push 2 and the Novation Controller XL to perform this session in realtime. The fader assignment is as follows (see Figure 29 above):

The pinky finger of the left hand controls the Kick-1 (Fader 1).

A second Kick-2 (Fader 5) is placed on the index finger of the right hand.

Next to the them, are audio tracks with effects; SimpleDelay (Fader 2) for the ring finger of the left hand and an Echo-1 (Fader 6) effect for middle the right hand. Furthermore, these audio tracks provide the spatialisation effect which is likely to be a good fit for this type of sonic material (containing higher frequencies than the Kick and Bass drum sounds), this decision is connected to the idea of ‘gravitational spatialisation’.

The middle and the index fingers of the left hand are connected to vocal, melodic or rhythmic audio content (Audio-1 and Audio-2) (Fader 3 and Fader 4).

An additional vocal, melodic or rhythmic audio loop is set for the ring finger of the right hand (Audio-3) (Fader 7).

The Echo-2 (Fader 8) effect is set for the pinky finger of right hand, and it will be set with spatialisation.

In order to implement improvisation to the 8 audio tracks, another Audio Effect Rack containing Filter, Reverb and Shuffling effects is set to the 3 rows of knobs above the 8 Faders from the Novation Controller.

In addition, the Novation has two kill switches knobs for the removal of Low and Mid (EQ Three effect) frequency content placed below the 8 Faders.

Thus, 3 audio tracks are spatialized around the dome of speakers on the middle and high ring of speakers and they are situated on track 2, 6 and 8. The other audio tracks (1, 3, 4, 5 and 7) are providing localized spatialisation on the Lower and Middle ring of speakers.

3.7 - Experimentation with Live Spatialisation

Throughout my research I have developed a compositional template that I implement in each work. As part of this, I have developed a spatialisation model that allows me to implement 3D sound movement into my works. This creative technique has enabled me to pre-set automated spatialisation trajectories that permit me to focus on the formal and improvisatory elements of my pieces. After several experiments using various hardware tools and plugins, my live spatialisation has come to focus on a pre-determined set of 3-4 audio tracks in which movement is controlled via an LFO moving in either a clockwise and counterclockwise direction around the middle and upper circles of 8 speakers. In addition, 4-5 audio tracks are fixed on the lower and middle circles of the SPIRAL Studio speaker configuration. I have tried composing with more than 5 audio tracks being spatialized simultaneously, however, the experiments were unmusical and did not convey my musical intention regarding how I wanted the work to unfold and develop. I have empirically found that 3-4 audio tracks of spatialisation offer clarity of spatial movement and a sense of sonic immersion that stimulate an active state of listening.

I have attempted to expand my spatialisation model for live performance by implementing direct control and manipulation of the spatial movement of selected audio loops. In order to execute this goal, I had to add another MIDI controller to my setup. This addition will increase the possibility of transforming the audio content both sonically and spatially. This will require further exploration and will take time to find new creative solutions and relevant mapping outputs for this device. So far, my experiments have comprised the evaluation of three Ableton Spatialisation plug-ins in addition to current chosen ones; Max Api Ctrl1 LFO and the Max Api SendsXnodes (See Figure 13). The recently added plug-ins are: Surround Panner (February 2018)[47], Spacer (September 2016)[48] and Envelop (April 2018)[49].

Figure 30 – Max for Live’s Surround Panner, 2019.

Max for Live’s Surround Panner plugin (see Figure 30 above) enables mixing sound for installations, theatres and performances, using multiple channel speaker setups in Ableton Live. It features the multi-speaker panning control of the X/Y axes. It is possible to create circular movement with the rotation control in 2D space. A focus control permits distinct positioning and speaker configuration. This plug-in is simple and intuitive to use but it has a limitation of only 8 outputs and my current setup requires 24 outputs. Thus, I have implemented only on the highest ring of 8 speakers. Because of this limitation, I have decided that if I had to perform on a smaller dome of speakers, I could potentially use it then. In order to circumvent this limitation, I have set 2 audio tracks to the higher ring of 8 speakers and 2 audio tracks on the middle ring. The result was adequate in regards of being to direct and locate the audio on the specific ring of speakers, but he conundrum arise with the decision of choosing between having a sound circulating where and when we want it. Furthermore, after moving the selected sound source it stays fixed at that same position if we are not moving it again as the piece progress, which is contrary to my spatialisation ethos; perpetual motion of sound in space. A positive quality to the Surround Panner is being able to provide a continuous circular motion to the sounds while selecting the rate of circular speed to an audio source, but this is also applicable to the current plug-in I am using (Max Api SendsXnodes), which has 24 channels of possible outputs. In order to compare my current modus operandi and the tested plug-ins, I have documented the live modulation of space versus my automated spatialisation. These tests are videos and sonic demonstrations that provides evidence that my designed automated spatialisation is as good if not better than the live modulation of space. The examination procedure was to record the live spatialisation with one of the tested plug-ins and, in order to compare with my approach, to remove the plug-ins from the audio recording and replace it with my method of designed spatial audio movements using the Max Api Ctrl1LFO and the Max Api SendsXnodes.

Listen with headphones:

Example 1 – Sebastian DeWay - Groove Society (Surround Panner)

Example 2 – Sebastian DeWay - Groove Society (Surround Panner – My Automation)

The Max Api SendsXnodes (See Figure 13) is a device based on the panning of audio content between adjacent output channels. I am using it in conjunction with the Max Api Ctrl1LFO in order to automate a selected trajectory to the center dial (audio loop). In order to expand on the possibility and the variety of sound manipulation and spatialisation, I have connected the AKAI MidiMix with the Sync Base parameter, which can select a rate of circular speed in the motion of the audio content around the chosen speakers. I have noticed that a rapid live motion of sound in space in combination with a Reverb plug-in can provide some interesting musical effects, which could potentially be included in my future performance setup. The comparative test of live modulation of space with the Base Sync from the Max Api Ctrl1LFO demonstrate that there are some benefits and some drawbacks to the performance: The possibility of direct motion with the instrument helps with on the fly spatialisation decisions but the overall quality of the sonic transformations is not enhancing the musicality of the performance.

Listen with headphones:

Example 3 – Sebastian DeWay - Groove Society (Max API Ctrl1LFO)

Example 4 – Sebastian DeWay - Groove Society (Max API Ctrl1LFO – My Automation)

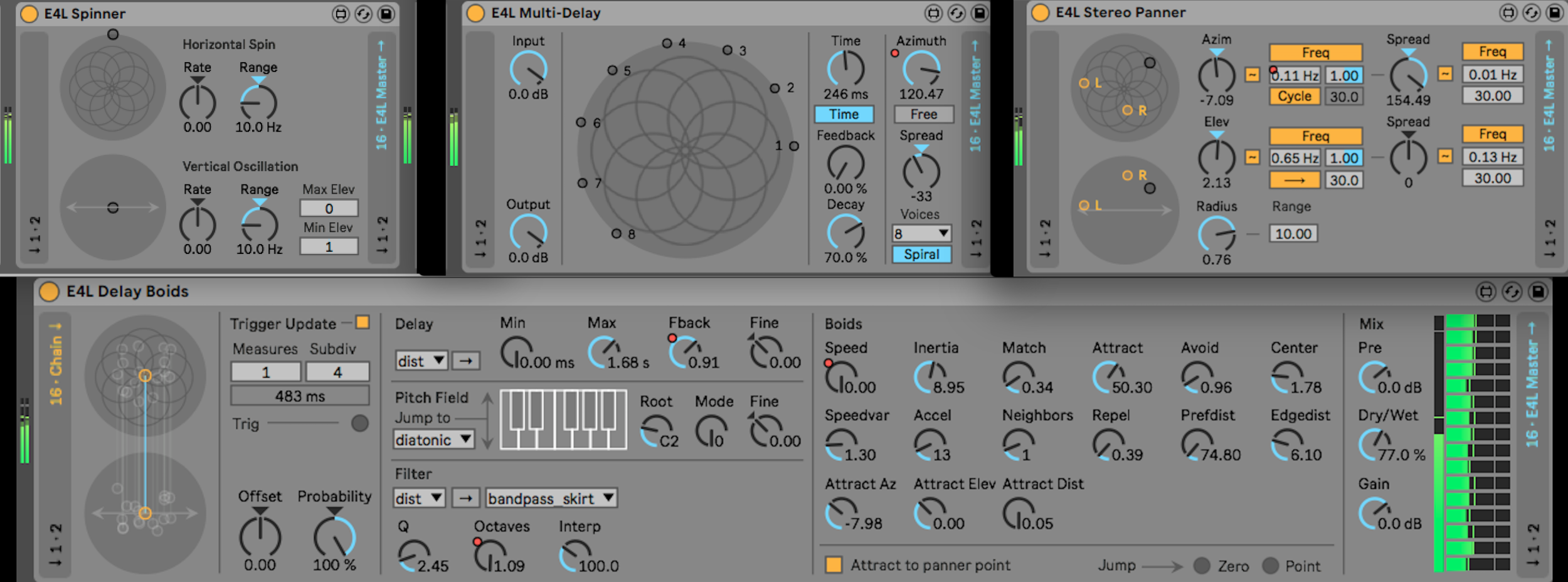

Figure 31 – Envelop for Live’s (E4L) Spinner, Multi-Delay, Stereo Panner and Delay Boids, 2019.

The Envelop (for Live) production tools enable composers to do sound placement in three-dimensional space. These spatial audio plug-ins can create immersive mixes for headphones and for multi-channel environments. I have experimented with several of the Envelop 4 Live (E4L) plug-ins (see Figure 31 above); the E4L Delay Boids, the E4L Spinner, the E4L Multi Delay and the E4L Stereo Panner. These are sophisticated tools that deserve consideration, they are efficient and easy to use but require practice in order to exploit them fully. Comparable to the live modulations of space done with the Base Sync of the Max Api Ctrl1LFO, the E4Ls can have a negative impact on the musicality of the performance if they are not controlled properly. Envelop tools were only available in the final months of this research, otherwise I would have definitely explored their potential since they are well suited for live spatial performance. The results between my spatialisation’ setup and the use of the Envelop tools are similar; some spatial instances are a better fitted with the E4Ls, and a certain clarity of spatialisation is perceptible while using my own designed automations on the M4L APIs.

Listen with headphones:

Example 5 – Sebastian DeWay - Groove Society (Envelop)

Example 6 – Sebastian DeWay - Groove Society (Envelop – My Automation)

Figure 32 – Spacer plugin, 2019.

The experimentation with the Spacer plug-in (see Figure 32 above) was not satisfactory since it provided only 8 channels of audio. Additionally, the Gain level was difficult to balance accordingly when moving the sound sources to the different speakers (outputs) in space. Furthermore, the audio outputs of Spacer do not permit a recording and a bounce of the working session in order to provide a sonic example of its use.

Overall, these tools will inspire further creation of spatial music and we can see that there is a growing interest from developers and audiences for spatialisation. I can see myself continuing to search for suitable tools for live modulation of space.